Research Poster

Research posters are often used at conferences in place of more formal presentations. Typically, posters are displayed in a large room, and presenters stand near them to give brief speeches or to answer questions. The audience members decide how much of the poster they want to read, if any. To attract and keep an audience’s attention, posters must be both intriguing and straightforward.

Your poster will probably be on display among many others, so it will be competing for the audience’s attention. Make it easy to comprehend quickly. A glance should reveal what research you’ve conducted and why. The key is an effective title. The title should be as clear as possible and include the issue and your approach to research. If the audience is more general, a catchy title can be effective, as in the first example, below. Otherwise, stick to a short, straightforward description of your work.

Ex. 1 “I Can’t Work with Women”: Gender & Student Writers’ Perceptions of Peer Tutor Competency

Ex. 2 The Effect of Gender on Student Writers’ Perceptions of Peer Tutor Competency

Ex. 3 The Role of Gender in Directive Versus Non-Directive Peer Tutoring Styles

The title should be the most prominent aspect of the poster and should be legible from approximately 3 meters (about 10 feet) away. Leave some space for your name and the name of your university or agency.

Introduction: Interest your reader in your topic and present a clear hypothesis. Placing your research in context of current scientific literature or problems can help the audience see its significance. Explain the research problem you are investigating and why it’s significant. If necessary, include background information and key terms. Consider including a graphic that connects to your hypothesis and illustrates your work’s focus.

Methods: Briefly describe methods and materials used in your research: often, these are better communicated through illustrations and photographs. Labeled drawings or photos can display your steps, and flow charts can show experimental procedures. You should also include your methods of statistical analyses and their effectiveness in testing your hypothesis.

Ex. Step 2. Intact seeds were selected from 25 cowpea varieties and a reference cowpea sample.

Ex. Step 2. Intact seeds were selected from 25 cowpea varieties and a reference cowpea sample.

Results: Describe results in quantitative and qualitative terms and directly state whether your hypothesis was confirmed. Use visual tools—tables, legends, graphs, and images—to illustrate your results.

Discussion: Discuss the conclusions of your research. First, briefly reiterate your hypothesis and results. Clearly and quickly state whether your hypothesis was supported, and why your findings are relevant and interesting. Describe alternative research methods, possibilities for future studies, or possible applications for your findings.

References: Include a references and/or an acknowledgement section. Give your email address or website, so audience members can contact you for more information.

punctuation are consistent; etc.)

Non-Parallel:

The alignment of content on the poster to left leads the viewer’s eye to the center of the poster. The poster on the right demonstrates that major graphics should be central to immediately grab the viewer’s attention.

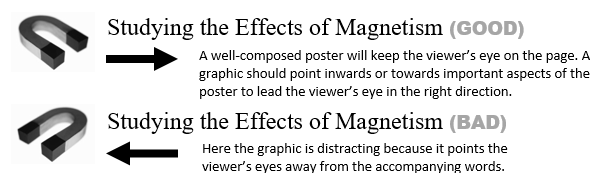

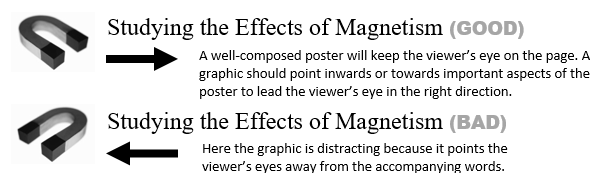

The following visual explains how graphics can affect the composition of a poster:

Make sure the poster looks as neat as possible by aligning the margins and spacing the content evenly. If the outer margins are tiny, you have too muchcontent and need to edit. Small margins look overcrowded, sloppy, and unprofessional, whereas areas of blank space, or “white space,” look professional and approachable:

Never use cutesy or decorative fonts like Comic Sans MS, Ravie, Chiller, or Gigi. You can use more than one font on the poster, but all fonts should complement each other and be use consistently. For example, put all of the sub-headings in the same font, rather than having each in a different font. Use a serif font, such as Times New Roman for body text, because serif fonts are easier to read in smaller sizes.

Color

Color can add interest to a poster, but be careful because it can also make it look unprofessional. Use bright colors only when emphasizing a point. Make sure the colors you choose fit within a unified, pleasant color scheme. Many websites offer premade color palates. The color of the content (especially the text) and the background should be high contrast (think black versus white) for maximum visibility.

Graphics

Graphics entice readers to look closer, while orienting them to the topic or content. Graphics should always connect to content: don’t add random pictures in an attempt to make the poster more interesting.

With any type of graphic, it’s important that the resolution of the image is high enough so that it can be printed without becoming pixelated (fuzzy). Many images copied from websites, especially small ones, are pixelated when printed, which looks unprofessional. (You also run the risk of copyright infringement when using images from the internet.) Use your own photographs and illustrations whenever possible to control the quality. Or obtain photos from stock photo websites, such as istockphoto.com or morguefile.com, which offer hundreds of high quality options. List the source for any photos you have not taken yourself. When using photographs, add a thin, hardly noticeable outline, or rule, to the image to create a cleaner look. For a change, consider using an entire photograph as the background (but make sure the content is legible).

Tips

It’s also helpful to check out some sample posters. Colin Purrington has written an excellent online resource for creating research posters: www.swarthmore.edu/NatSci/cpurrin1/posteradvice.htm.

Day, Robert A. and Barbara Gastel. How to Write and Publish a Scientific Paper. Westport: Greenwood Press, 2006.

Goldbort, Robert. Writing for Science. New Haven: Yale University Press,2006.

Audience

Knowing your audience will help you determine the poster’s content and style. Consider whether the poster will complement your speech or if it will stand alone. If it will be displayed for people familiar with your topic, it’s fine to use specialized terms, jargon, and a detailed depiction of your results. However, posters intended for a more general audience should avoid jargon and should stress results and application over methods and data analysis.Your poster will probably be on display among many others, so it will be competing for the audience’s attention. Make it easy to comprehend quickly. A glance should reveal what research you’ve conducted and why. The key is an effective title. The title should be as clear as possible and include the issue and your approach to research. If the audience is more general, a catchy title can be effective, as in the first example, below. Otherwise, stick to a short, straightforward description of your work.

Ex. 1 “I Can’t Work with Women”: Gender & Student Writers’ Perceptions of Peer Tutor Competency

Ex. 2 The Effect of Gender on Student Writers’ Perceptions of Peer Tutor Competency

Ex. 3 The Role of Gender in Directive Versus Non-Directive Peer Tutoring Styles

The title should be the most prominent aspect of the poster and should be legible from approximately 3 meters (about 10 feet) away. Leave some space for your name and the name of your university or agency.

Organization

Posters should have a natural and obvious organization that flows easily. Often, the best organization for research topics is the Introduction, Methods, Results and Discussion (IMRAD) format used in much scientific writing. Each section should be no more than 200 words, preferably fewer.Introduction: Interest your reader in your topic and present a clear hypothesis. Placing your research in context of current scientific literature or problems can help the audience see its significance. Explain the research problem you are investigating and why it’s significant. If necessary, include background information and key terms. Consider including a graphic that connects to your hypothesis and illustrates your work’s focus.

Methods: Briefly describe methods and materials used in your research: often, these are better communicated through illustrations and photographs. Labeled drawings or photos can display your steps, and flow charts can show experimental procedures. You should also include your methods of statistical analyses and their effectiveness in testing your hypothesis.

Ex. Step 2. Intact seeds were selected from 25 cowpea varieties and a reference cowpea sample.

Ex. Step 2. Intact seeds were selected from 25 cowpea varieties and a reference cowpea sample.Results: Describe results in quantitative and qualitative terms and directly state whether your hypothesis was confirmed. Use visual tools—tables, legends, graphs, and images—to illustrate your results.

Discussion: Discuss the conclusions of your research. First, briefly reiterate your hypothesis and results. Clearly and quickly state whether your hypothesis was supported, and why your findings are relevant and interesting. Describe alternative research methods, possibilities for future studies, or possible applications for your findings.

References: Include a references and/or an acknowledgement section. Give your email address or website, so audience members can contact you for more information.

Style

To make the poster readable, keep it concise. A bulleted list gives information in a less wordy format, but make sure all items in the list are parallel, (e.g., each item begins with the same part of speech; capitalization andpunctuation are consistent; etc.)

Non-Parallel:

- Test hypothesis

- Data is collected

- Then you write the conclusion

- Test hypothesis

- Collect data

- Write conclusion

Design

Poster layouts should be easy to follow and visually appealing. Microsoft PowerPoint is commonly used to design posters (dimensions can be adjusted under design>page setup) because content can be easily formatted and re-arranged. Before you start, determine the required dimensions and the type of material you will be using. Some posters are split into separate parts and then assembled for presentation; others are printed directly onto a poster. If you’ll be traveling to the presentation, think about how you’ll transport the poster.Layout

Present the content in a logical order. Since English speakers read from left to right and from top to bottom, organize so that the information you want people to read first appears in the left, top corner. The title should be the most prominent aspect of the poster. The arrangement of graphics and content should hold the viewers’ attention and lead them through the content visually.

The alignment of content on the poster to left leads the viewer’s eye to the center of the poster. The poster on the right demonstrates that major graphics should be central to immediately grab the viewer’s attention.

The following visual explains how graphics can affect the composition of a poster:

Make sure the poster looks as neat as possible by aligning the margins and spacing the content evenly. If the outer margins are tiny, you have too muchcontent and need to edit. Small margins look overcrowded, sloppy, and unprofessional, whereas areas of blank space, or “white space,” look professional and approachable:

Text

The text should be large and easy to read because people may be looking at the poster from across a crowded room. (Everything should be legible from three feet away.) If you cannot make the text large enough without running out of space, chances are you need to edit. If you have large chunks of text, break them up into manageable bits. It’s usually best to align text to the left rather than centering it.Never use cutesy or decorative fonts like Comic Sans MS, Ravie, Chiller, or Gigi. You can use more than one font on the poster, but all fonts should complement each other and be use consistently. For example, put all of the sub-headings in the same font, rather than having each in a different font. Use a serif font, such as Times New Roman for body text, because serif fonts are easier to read in smaller sizes.

Color

Color can add interest to a poster, but be careful because it can also make it look unprofessional. Use bright colors only when emphasizing a point. Make sure the colors you choose fit within a unified, pleasant color scheme. Many websites offer premade color palates. The color of the content (especially the text) and the background should be high contrast (think black versus white) for maximum visibility.

Graphics

Graphics entice readers to look closer, while orienting them to the topic or content. Graphics should always connect to content: don’t add random pictures in an attempt to make the poster more interesting.

With any type of graphic, it’s important that the resolution of the image is high enough so that it can be printed without becoming pixelated (fuzzy). Many images copied from websites, especially small ones, are pixelated when printed, which looks unprofessional. (You also run the risk of copyright infringement when using images from the internet.) Use your own photographs and illustrations whenever possible to control the quality. Or obtain photos from stock photo websites, such as istockphoto.com or morguefile.com, which offer hundreds of high quality options. List the source for any photos you have not taken yourself. When using photographs, add a thin, hardly noticeable outline, or rule, to the image to create a cleaner look. For a change, consider using an entire photograph as the background (but make sure the content is legible).

Tips

- Do not use acronyms or shorthand that those outside your discipline won’t understand.

- See if a friend outside of your discipline can understand your poster.

- Use Italics instead of underlining to make the poster look cleaner.

- Proofread the poster carefully for factual mistakes or grammar and spelling errors, and then ask a friend to review it as well.

- Put the poster up on a wall and ask friends for their feedback.

- Be creative and think beyond the obvious. For example, if your research involves a new kind of fiber, bring a sample for people to feel. Or create a 3-D model to better demonstrate your project. Or bring a laptop and play a short video clip related to your research.

- Provide a brief handout or summary sheet for audience members to take away with them.

It’s also helpful to check out some sample posters. Colin Purrington has written an excellent online resource for creating research posters: www.swarthmore.edu/NatSci/cpurrin1/posteradvice.htm.

References

Alfano, Christine L. and Alyssa J. O'Brien. Envision: Persuasive Writing in a Visual World. New York: Pearson Longman, 2005.Day, Robert A. and Barbara Gastel. How to Write and Publish a Scientific Paper. Westport: Greenwood Press, 2006.

Goldbort, Robert. Writing for Science. New Haven: Yale University Press,2006.